Can You Really Critique Art?

Author: Mukund Shyam

Published on: 04 09 2025

So a few weeks ago, I ran into this short on my YouTube page. Its a video of Fantano critiquing Djesse Vol 4 by Jacob Collier. At this point, I’d been in a bit of a Fantano rabbithole, randomly running into him on my feed, and much to my annoyance, getting very engaged by his content. One thing cannot be denied about Anthony Fantano—he is unbelievable at grabbing—and keeping—your attention.

Suffice to say, Fantano dunked on this album completely. And I got pulled into a rage-induced search panic, when I went through a number of albums that I really enjoyed over the past year or two, only to realise that he disliked those as well (albeit seemingly to a lesser extent). And these included albums like The Secret Of Us, which I considered to be one of the best pop albums I’d discovered this year.

Now, I was annoyed, obviously—not only due to the realisation that anyone can dislike “my” music, but also Fantano’s stature as a respected music critic in the online space giving his opinions more weight than others'. And this isn't an experience that is new to me; one of the best book YouTubers on the platform, in my opinion, Jack Edwards (a guy who’s taste I trust immensely) rated my favourite book of all time (Turtles All The Way Down) a 2.5 out of 5. Taylor Swift’s The Tortured Poets Department wasn’t exactly received with widespread critical acclaim, but I found it to be an extremely good album.

Afterward, I ran into a video by Mic the Snare, titled “In Defence of Jacob Collier” which sparked a string of thoughts that led eventually to this piece. Basically, Mr. Snare’s thesis is that a number of critiques of Collier are unfounded; a large number of these critiques arise from a mismatch between the expectations of the critic and the value proposition of the artist. For instance, many criticise Collier’s songs for having poor songwriting, but that’s seemingly not what Collier provides to the music corpus—instead offering crazy production, interesting use of music theory, raw chaos, etc. And this I agreed with.

But I don’t think this is a comprehensive enough critique of music criticism (ironically).

Part 1: An Intro

Before I begin, though, I want to tell you why I care about this stuff. I want to tell you where I’m coming from, what my biases are, and what kind of things I think are informing this opinion. I don’t claim that this is some universal truth in the slightest—forgive the postmodern in me for showing itself. Finally, it's important as a philosophy major for me to state that I have absolutely no knowledge of aesthetics; this is almost certainly a question that has been theorised of to a very high level in the field. Maybe my views will change when I do my module on aesthetics in university.

I’m a musician myself, and I think that in many ways has made me extremely wary of criticising music. I feel like I can see the work put into every piece of music, whether or not it’s my thing—perhaps everything except that god-awful Keemstar song. I feel like every piece of art has merit, whether or not I like it. Plus, having a general post-modern ethical and epistemic worldview makes you critique all forms of objectivity; thus, that plays an obvious role here.

Part 2: A Basic Critique

Building on what Mic The Snare mentions in his video, it’s easy to come to a basic critique of art criticism.

The only valid way to critique art, in this framework, is by comparing it to the intentions of the creator. Listen to this—Charli xcx's hit single Von Dutch. Von Dutch One way to criticise this piece is by suggesting that it’s mixed badly because the bass was too intense.

That seems to be, obviously, a bad critique; in many ways, the overwhelming bass is part of the appeal of this song. It's an extension of rave culture, while also working to serve as commentary on the omnipresence of hedonism and the impact of contemporary socio-economic society on people's lives.

Without the overwhelming bass, Von Dutch loses a lot of its flair; thus, one cannot critique art simply based on whether or not it follows a certain set of technical norms (that are, in many ways, arbitrary and made to be broken).

Most art criticism seems to arise from a mismatch between critic and audience expectation and the output, rather than a mismatch between artist intention and the output.

You need to consider the intentions of the artist, and compare the output to the intentions of the artist to truly critique art; and that, in my opinion, is the nuance that is missing from a lot of art criticism; people aren’t truly criticising art, but rather are asking for a different thing (and this is what Mic the Snare argues as well).

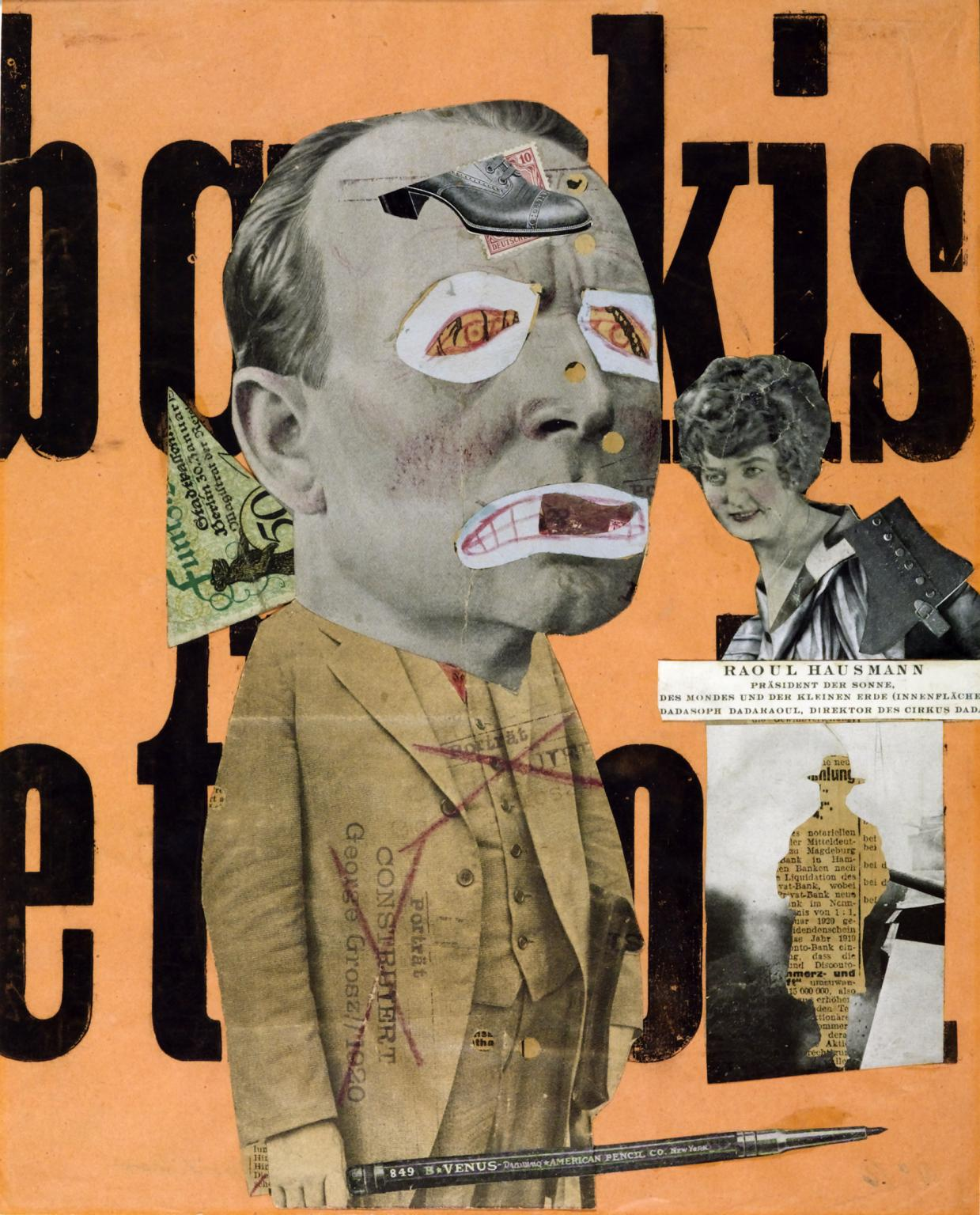

Take Dadaism, for example. Dadaism was a modern art movement that was overtly avant garde. It was, by its very construction, subversive; it was meant to critique the various norms in place at the time. Take a look at this piece, “The Art Critic” by Raoul Hausmann.

In the current landscape of art critique, this could be considered “bad art” because it is not realistic in the slightest. But that’s kind of the point! It didn’t make sense, and it wasn’t supposed to. It dismantled the order and rationality of post-enlightenment war-time. It was meant to be meaningless and provocative! Thus, suggesting it’s bad because it’s not realist is just completely invalid.

Alternatively, you could criticise the aims of the artist themselves; but I think that puts one on a very slippery slope. All art has meaning; I think critiquing the aim of the artist as being “wrong” or “unnecessary” is functionally misleading. Art is an inherently radical, exciting, and rebellious act; critiquing the aims of artists fundamentally goes against this. Artists ought to be able to do anything they want to, in a broad sense at least.

Obviously, there is a lot more to talk about the nature of art, but for now, I think this is a good enough place to start of with. The only true critique of art is one that compares the output of the artist to their intentions; while most tends to compare the output of the artist to the reader’s expectations. Since it's basically impossible to understand the true aims of the artist, you can basically never critique art. Theoretically, one could also critique the aims of the artist, but in practice, this is impossible—or at least problematic—since art is inherently rebellious and non-conformist.

Part 3: A More Comprehensive Critique

Honestly, to me, this feels like a basic and incomplete critique for one main reason: it imagines the consumption of art as being completely objective. Plus, this suggests that art critics and culture writers are fundamentally useless individuals since the work they do is ontologically meaningless; which I think is a ridiculous proposition.

The basic critique I offered prior assumes an objective reading of the output to be able to compare that to the artist’s intentions. Forget being able to judge the artists intentions, I believe that it is impossible to objectively read the output.

John and Hank Green mention this explicitly, perhaps most explicitly in an episode of the Dear Hank and John podcast. “Here is the truth of any book and any media. Right? We need the reader or the viewer or the listener or whatever to be generous. To bring their whole self to it. And that’s asking a ton, and a lot of times you can’t bring your whole self to a book because you’re feeling snarky, and angry, and you’re disgusted with the world, and that seeps into your reading experience.” - John

Art is not just consumed, but interpreted. When one consumes art, one’s own life experiences, biases, and preferences affect the way in which it is interpreted.

A basic counter to this position is the idea that the interpretation of art is based purely on evidence (eg. technical proficiency, emotional weight). The true, implicit meaning of art can be understood by analysing and weighing evidence generated by the art against each other. And to that, I respond: how do you weigh the evidence?

Take the example of the Edgar Allan Poe short story “The Tell-Tale Heart”. I encourage everyone to read it but basically, it’s the story of a guy who kills a man because his glass eye freaks him out. Eventually, at the end—spoiler alert—despite no one suspecting him, he confesses to the murder.

Now, the central figure in this story is an unreliable narrator. He is almost certainly mentally ill. And this raises the question of whether or not the murder actually took place: is he schizophrenic, and hallucinated the whole set of events, or did he actually kill the neighbour? Who knows. How do you weigh the evidence? By the number of points you have on each side? How do you know how important each piece of evidence is to that particular narrative? That is a fundamentally subjective process.

This also solves the question of aesthetics. The prior critique doesn’t consider aesthetic value; this acknowledges differences in aesthetic preferences—I like pop, my brother likes rock—as affecting the way in which art is consumed and interpreted.

Additionally, this method of understanding art allows for varying analyses of art as being equally valid—for instance, I like Turtles All The Way Down because I read it at a very specific time in my life. Same with Paper Towns. The temporal context in which the art was consumed certainly played an important role in my experience—and opinions—of it.

And critically, it suggests that it is impossible to objectively critique art; the criticisms all arise from differences in preference, bias, and context. Nothing, therefore, can make art truly “good” or “bad”.

Outro

Where do we go from here? I’m not entirely sure.

I don’t want to suggest that art criticism is purely harmful, or even that it’s broadly unhelpful. Everything said and done, I see a lot of value in art criticism; how on Earth will I know what to spend my (extremely limited) time on?

I think the main issue here is the perceived objectivity associated with art critique. Critics' opinions, in the audience's (and oftentimes their own) eyes, seem to be given some kind of larger-than-life weight. Like their opinions are somehow more valid than that of “normal” consumers. Perhaps this is the issue with award shows like the Grammys as well; we act as if they are the speakers of gospel about what art is the “best” despite them having a set of preferences and biases that oftentimes don’t align with those of the “general public” (see also: the historic snubbing of artists of colour and genres like hiphop in the “big 4 categories”).

In this light, I claim that art criticism cannot be objective.

Perhaps art criticism must go beyond notions of objective “goodness” or “badness”. I know this does sound like postmodern garbage—perhaps because in many ways it is—but I truly believe in it. The function of art criticism is simply to offer a certain interpretation of a piece of art—an interpretation that is valuable simply because of the large corpus of work art critics have consumed. It is their experience that makes art critics so good at their jobs, not because they're somehow "better" at understanding art than the rest of us. Maybe capitalism plays a role in pushing critics to act as arbiters of truth; by doing so, they can separate themselves from the people who are simply un-objective interpreters of art.

Furthermore, the function of art criticism—and more broadly, discussions about art—seems to be more to generate a number of varied, interesting, interpretations of art; thereby setting the stage for further discourse to take place. Discussions about art help take it from the artist to the consumer, turning it from an individual process of creation to a collective process of interpretation. Side note: in this context, the view that art, after being released, belongs to its consumers seems to be further supported.

To conclude, I think it should be extremely possible to obtain the benefits of art criticism as society without having to fall into the plights of falsely perceived objectivity. Objectivity cannot exist—particularly in the context of art interpretation—not simply because people cannot compare artistic output to artistic intention, but also because consumers cannot consume art in isolation; art interpretation is contingent on the social, emotional, and economic contexts within which it is consumed.

Further Reading

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/dada-115169154/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ksP1hsyup1w

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2ZlrHyzIwcI&list=TLPQMjgwMTIwMjXJmRAWzsCI4A&index=2

- https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/d/dada

- https://www.moma.org/collection/terms/dada

- https://www.youtube.com/@jack_edwards

- https://www.youtube.com/@theneedledrop